20.109(F07): siRNA design

Introduction

In the previous experimental module, your work has focused on DNA. In this experimental module, RNA gets the spotlight. While DNA has one job, to encode the genetic information of a cell, RNA is remarkably versatile. The scientific literature on RNA includes reports of enzymatically-active RNAs (indeed our DNA/RNA/protein world is thought to have evolved from an RNA-based one), and RNAs that directly regulate transcription and translation. RNA has long been used as a readout for gene expression but has only recently been appreciated as a tool for manipulating gene expression.

The term “gene expression” does not refer to happy faces on the DNA as the name implies but is a term used to describe how much of a gene product is synthesized by a cell. In liver cells, expression of genes for liver-specific proteins is high and brain-specific genes is low. Many diseases arise from mis-expression of genes. For example, cancer cells make lots of proteins they shouldn’t and grow without limits because the normal regulators of gene expression are broken or malfunctioning.

Gene expression is often regulated at the level of transcription and examples of transcriptional regulation are numerous. The bacterial lac operon is the classic example, using DNA-binding proteins to both enhance and repress transcription of the operon. However, many examples of post-transcriptional regulation exist and recently studies in worms (C. elegans), fungi (e.g. N. crassa), plants (e.g A. thaliana) and flies (D. melanogaster) revealed a mechanism of gene silencing called RNA interference (RNAi), in which repression is mediated by double stranded RNA (dsRNA). The powerful genetic tools available for these organisms led to the rapid identification of many genes important for gene silencing by dsRNA. RNAi studies have progressed rapidly through a combination of genetics, molecular biology and biochemistry to become one of the most exciting areas in gene expression research.

RNAi can silence genes in mammalian cells although other expression effects, not specific for the targeted gene, can be seen. Mammalian cells seem to interpret dsRNA as a viral infection and initiate a response to protect themselves from it. Shorter dsRNAs, sensibly called short interfering RNAs (“siRNAs”) are 21-25 nucleotides long and can bypass the cell’s surveillance system. Indeed, siRNA has silenced genes in many types of cultured mammalian cells, including neuronal, epithelial and fibroblast cells.

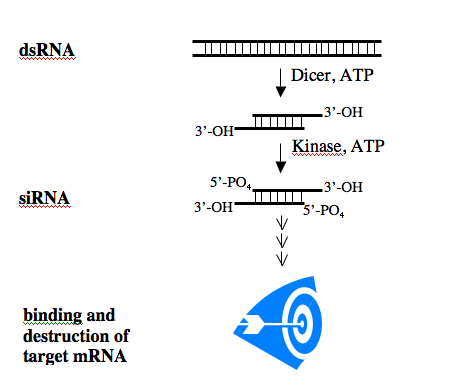

The biochemistry of the RNAi pathway is relatively well characterized and the general features of siRNAs are known. To induce RNAi, a dsRNA is processed within the cell to an siRNA which then binds to its single-stranded mRNA target. The binding leads to the destruction of the mRNA, effectively silencing gene expression.

After processing, siRNAs possess a sense and an antisense strand. Their 3’ ends overhang by 2 bases and each strand has a 5’ phosphate group and a 3’ hydroxyl. By convention, the siRNA duplexes are described by the sense strand, with the first position of the 5’end referred to as position 1. This usually corresponds to position 19 or so on the antisense strand.

In this experimental module, RNAi will be used to silence gene expression in a mammalian cell line. Today you will design an siRNA to silence luciferase, a gene not normally found in the cell line we’ll study. Later in this experiment, you will introduce the gene and the siRNA to observe targeted and off-target effects of RNAi.

Protocol

The class will be split in 1/2 today, with 6 people starting in the cell culture facility and 6 will start with siRNA design. Midway through class, you'll switch places.

Part 1: siRNA design

Although the biochemistry of dsRNA processing is well understood, less is known about the features that make some siRNAs potent silencers of gene expression and other siRNAs useless. Many times researchers will design four or more siRNAs for a target gene and find only half of them work well. In designing siRNAs, the messenger RNA’s sequence must be known, but choosing which region to target is mostly guesswork. The siRNA sequence must bind an invariable region of the gene. It has been reported that a one basepair mismatch between the target and siRNA can convert an effective inhibitor into a useless one. Conversely, siRNAs can work promiscuously and silence non-target genes, leading to effects on genes that bear some sequence similarity to the targeted one. Some reports suggest that as little as 14 base pairs of complementarity can cause an siRNA to silence an off-target gene.

Design of siRNA against Renilla luciferase

Renilla reniformis is a soft coral, often called a sea pansy, which washes up on Florida beaches after a storm. It will bioluminesce when disturbed due to GFP and a gene for a second light-making protein, luciferase. The biochemistry of the luminescence will be described in detail a few days from now. Today, you and your partner will examine Renilla’s gene for luciferase and will be assigned one portion to target for RNAi.

| Team Color | Target |

|---|---|

| Green | R_luc bp 1-156 |

| Purple | R_luc bp 157-312 |

| Red | R_luc bp 313-468 |

| Blue | R_luc bp 469-624 |

| Pink | R_luc bp 625-780 |

| Yellow | R_luc bp 781-936 |

Begin by retrieving the sequence of the gene you hope to silence. Open a web browser program and go to the Promega homepage. The Renilla luciferase gene was fully sequenced in 1991 but the clone you will study is expressed on a plasmid that is commercially available from Promega.

Search the site for psiCHECK2, the name of the plasmid with the Renilla luciferase gene. The “psicheck2 vector” link will retrieve the plasmid sequence with some landmark information at the top of the page. Copy the Renilla luciferase gene sequence into a new MSWord document (remember that the sequence should begin ATG and end with a stop codon. It will be 935 bases long) then trim the sequence to the area of the gene you have been assigned to target. This direction is in bold because people in the past have forgotten to do this!!

Open a new window browser window and go to the Ambion homepage. Like Promega, Ambion is a life sciences company selling many useful products for biological research. Ambion is particularly well regarded for its support of RNAi technology. You will use their search algorithm to assist in your siRNA design. This algorithm is found through their “RNAi resource” link. Under “siRNA design tools” you can click on “siRNA Target Finder” to get started. This page has lots of important information to read and good links to follow.

When you are ready to begin the design of your siRNA, paste your sequence from the MSWord document you started into the box that is near the bottom of the webpage. Delete any numbers once you’ve pasted the sequence. Choose “ends with TT.” Choose “all G/C contents.” Since your siRNA will be chemically synthesized, constrain the sequence to avoid 4 or more Gs or Cs in a row.

After you submit your query, several target sequences will appear as a list at the bottom of the webpage. The candidate sequences are listed according to where they bind the target mRNA, one parameter that has been shown to have no effect on siRNA efficacy. To decide which siRNA candidate on the list is most likely to silence luciferase specifically, copy each target sequence into a separate cell of a new Excel worksheet. You should also paste the sequence you queried.

For each siRNA candidate sequence, consider and record the following:

- What is the G/C content of the candidate? 30-50% G/C tends to work best. Some of the programs used in the next step will also return information on the G/C content of your sequence.

- Is the sequence likely to form secondary structures? These might make them difficult to process or unlikely to bind their target mRNA. The easiest predictors of secondary structure are the melting temperature, Tm, of the dsRNA and the free energy of the sequence. Tm can be calculated by pasting the sequence into a web-program available through Integrated DNA Technologies. Be sure the target type is set to RNA. There are several web-based programs available to predict RNA secondary structure and calculate its free energy. One such program is here. Another site to use for comparison is OligoCalc which will return Tm, G/C content and free energy calculations.

- What is the similarity of each target sequence to other mRNAs in mouse cells? Such sequence similarity is an important consideration since an siRNA can be specific for its target only if it fails to base pair with mRNAs from other genes. The Ambion list of candidate sequences has a BLAST link for each target sequence. Follow each link and query the "Mouse genomic + transcript" database since these siRNAs will be transfected into a mouse cell line. For each BLAST result scroll through the list for any mRNAs that have 16-17 contiguous bases of homology with the siRNA candidates and enter the identity of these genes into your Excel spreadsheet.

You should now be able to identify the best siRNA candidate sequence. Please print out three copies of your Excel spreadsheet and circle your choice of siRNA. Turn in one copy and keep the others for the assignment that is due next time when you return to lab to transfect the sequence you have chosen as well as the luciferase reporter plasmid into cells next time.

Part 2: Introduction to cell culture

In the past century, we have learned a tremendous amount by studying the behavior of mammalian cells maintained in the laboratory. Tissue culture was originally developed about 100 years ago as a method for learning about mammalian biology. The term tissue culture was originally coined because people were doing exactly that, extracting tissue and letting it live in a dish for a short time. Today, most tissue culture experiments are done using cultured cells. Much of what we know about cancer, heritable diseases, and the effects of the environment on human health has been derived from studies of cultured cells.

What types of cells do people study, and where do they come from? Cells that come from a tissue are called primary cells, because they come directly from an animal. It is very difficult to culture primary cells, largely because primary cells that are placed in culture divide a limited number of times. This limitation in the lifespan of cultured primary cells, called the Hayflick limit, is a problem because it requires a researcher to constantly remove tissues from animals in order to complete a study. To get around this problem, people have studied cells that are immortal, which means that they can divide indefinitely.

One type of familiar immortalized cell is the cancer cell. Tumor cells continuously divide allowing cancer to invade tissues and proliferate. Cancer cells behave the same way in culture, and under the right conditions, cells can be taken from a tumor and divide indefinitely in culture. Another type of immortalized cell is the embryonic stem cell. Embryonic stem cells are derived from an early stage embryo, and these cells are completely undifferentiated and pluripotent, which means that under the right conditions, they can become any mammalian cell type. Mouse embryonic stem cells have become a valuable research tool, and it is this cell type that we will be using for this experimental module.

The art of tissue culture lies in the ability to create conditions that are similar to what a cell would experience in an animal, namely 37°C and neutral pH. Blood nourishes the cells in an animal, and blood components are used to feed cells in culture. Serum, the cell-free component of blood, contains many of the factors necessary to support the growth of cells outside the animal. Consequently, serum is frequently added to tissue culture medium, although serum-free media exist and support some types of cultured cells.

Cultured mammalian cells must grow in a germ-free environment and researchers using tissue culture must be skilled in sterile technique. Germs double very quickly relative to mammalian cells. An average mammalian cells doubles about once per day whereas a bacterium is able to double every 20 minutes under optimal conditions. Consequently, if you put 100 mammalian cells and 1 bacteria together in a dish, within 24 hours you would have ~200 unhappy mammalian cells, and about 100 million happy bacteria! Needless to say, you would not find it very useful to continue to study the behavior of your mammalian cells under these conditions!

Each of you will have a 25 cm2 flask of mouse embryonic stem (MES) cells that you will use to seed a six-well dish. You and your partner will seed the dishes at different concentrations so you should decide who will seed at 1:100 and who will seed at 1:400.

- Prewarm all the required reagents in the water bath.

- Look at your cells as you remove them from the incubator. Look first at the color and clarity of the media. Fresh media is reddish-orange in color and if the media on your cells is yellow or cloudy, it could mean that the cells are overgrown, contaminated or starved for CO2. Next look at the cells on the inverted microscope. Note their shape and arrangement in the dish and how densely the cells cover the surface.

- Move the cells into the sterile hood, as well as the PBS, trypsin, and media that you will need. One of the greatest sources for TC contamination is moving materials in and out of the hood since this disturbs the air flow that maintains the sterile environment inside the hood. Anticipate what you will need during your experiment to avoid moving your arms in and out of the hood while your cells are inside.

- Aspirate the media from the cells.

- Wash the cells by adding 5 ml PBS. Tip the flask back and forth to rinse all the cells, and then aspirate the liquid out of the dish.

- To dislodge the cells from the dish, you will add trypsin, a proteolytic enzyme. Using a 2 ml pipet, add 2 ml of trypsin to the flask. For one minute precisely (use your timer), tip the flask in each direction to distribute the trypsin over the cells then aspirate the trypsin off the cells. Incubate the cells (“dry”) at 37° for 10 minutes, again using your timer to precisely time this incubation.

- While you are waiting, you can add 1 ml of gelatin to each well of a six-well dish. This should be done in the sterile hood with sterile technique. The gelatin will be removed before you seed the dish with your MES cells but it is important to pre-treat the dish this way. The gelatin must remain in the wells for at least 10 minutes.

- With a 5 ml pipet, add 6 ml of media to the trypsinized MES cells and pipet the liquid up and down (“triterate”) to remove the cells from the plastic and suspend them in the liquid. Remove a small amount of the liquid to an eppendorf tube and take it to the inverted microscopes.

- Fill one chamber of a hemocytometer with 10 ul of the cell suspension. This slide has an etched grid of nine large squares. The square in the center is further etched into 25 squares each with a volume of 0.1 ul and 16 tiny chambers (4x4 pattern). The concentration of cells in a sample can be determined by counting the cells that fall within the 4x4 pattern and then multiplying by 10,000 to determine the number of cells/ml. You should count the cells in the four corner squares of the 25 square grid, then average the numbers to determine the concentration of cells in your suspension.

Counting cells using a hemocytometer - You and your partner will seed at different concentrations. Decide if you will try the 1:100 or 1:400 dilution and add the appropriate amount of cell suspension to 10 ml of media in a 15 ml conical tube.

- Remove the gelatin from the six-well dish you have prepared and add 3 ml of your cell dilution to each well. Be sure to label your dish with your name, today’s date, the cell line (called “J1”) and the type of media you have used. Return your cells to the incubator.

- Aspirate any remaining cell suspensions to destroy them and clean up the hood. Dispose any vessels that held cells in the Biohazard waste and any sharps in the grey bins. The next group who uses your hood should find the surfaces wiped down, no equipment left inside, the sash closed and the germicidal UV lamp on.

DONE!

For next time

1. Ambion does not have the only siRNA design program. Compare the siRNA design criteria used by Ambion to those followed by another life sciences company, Dharmacon, which also specializes in RNAi technology. The Dharmacon search algorithm is based on the criteria for their siRNA design rules described by Reynolds et al. in Nature Biotechnology 2004; 22(3): 326-330. Decide how your siRNA candidates from the Ambion design algorithm rank using the Dharmacon criteria.

2. Calculate the number of cells in each well of your six-well dish. The following rules of thumb and guesses should be used for the calculation (note: the answer to this question will be one number...the rules of thumb all apply to that calculation):

- only 25% of the cells are able to stick and proliferate (this is called a 25% plating efficiency).

- the doubling time for the cells is 24 hours.

- the cells take 24 hours to recover from trypsin treatment before they begin doubling.

3. Your major assignment for this experimental module will be a formal lab report describing your work. The requirements for this report are detailed on the class wiki. Start by reading these guidelines carefully. You'll write part of the introduction today, first reading the relevant primary literature, and then writing three paragraphs according to the suggested scheme below. This scheme is just a rough framework to help you organize your thoughts. Naturally you are free to apply your personal style and writing approach. One thing everyone must do: keep track of the sources for your information to properly reference them in your final paper.

- Paragraph 1: most general of all. You don't have to start with the dawn of creation or how the first cell came to exist but you might consider framing the experiments around some larger questions like:

- why is gene expression important?

- how does the cell regulate gene expression?

- what experiments are useful for looking at gene expression?

- Paragraph 2: introduction to RNAi. This paragraph can't possibly cover all that's known about RNAi but some relevant and interesting aspects you might address are the:

- what relevant aspects of RNAi have been described? what types of RNAi are known?

- what makes a successful RNAi?

- how widely is RNAi used as a gene regulation mechanism: are mouse cells the only cell type using RNAi? is it used to regulate every gene in the genome?

- biochemistry of the RNAi machinery: names of subunits, how these were identified, are they all necessary for RNAi activity? are there other functions for any of the RNAi machinery? shared subunits with other chromatin remodelers?

- genetics of the complex: what happens when you delete subunits? what about pairwise deletions? are there traditional phenotypes associated with SAGA mutations? are there disease states associated with mutations in any of the subunits in organisms more complex than yeast?

- structure of the complex: how was this determined? are there other structural views that are supportive or contradictory? does the structure support any genetic or biochemical data?

- are the details of the process fully agreed on? are there contradictory models or studies?

- Paragraph 3: introduction to the experiment you'll perform. You've been assigned to target a particular area of the luciferase gene. You'll have to explain what that is, what the gene does, how you will know if your RNAi worked and what you're looking over.

You and your lab partner can and should discuss the papers you find and you should help eachother understand them. You can also ask the teaching faculty if you are unclear on the details of some technique you read about. When it comes time to write, you must do so on your own. You and your lab partner will hand in individual assignments. Please submit this part of the assignement electronically to nkuldell and nlerner AT mit DOT edu. Good luck and have fun!

Reagents list

Trypsin

- 0.25% Trypsin

- 1 mM EDTA

D-PBS

- Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline

J1 ES Cell Culture Medium

- DMEM (high glucose) with:

- 100 U/ml Penicillin/Streptomycin

- 0.3 mg/ml Glutamine

- 0.1 mM BME

- 1 mM Non-Essential Amino Acid (NNEA)

- 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Atlantic Biologic, Inc., Atlanta, GA)

- Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) - LIF helps stem cells maintain their undifferentiated state

Gelatin

- 0.1% TC-grade gelatin prepared in H2O

- Gelatin is a protein prepared by partial hydrolysis of collagen