20.109(S08):Data analysis (Day7)

Introduction

This is it, folks! Moment of truth. Time to find out how the proteins that you worked so hard to make, purify, and test really behave. Although you should be able to produce reasonable titration curves by following the example of Nagai, the introduction/review of binding constants below may help contextualize your analysis.

Let’s start by considering the simple case of a receptor-ligand pair that are exclusive to each other, and in which the receptor is monovalent. The ligand (L) and receptor (R) form a complex (C), which reaction can be written

[math]\displaystyle{ R + L \rightleftharpoons\ ^{k_f}_{k_r} C }[/math]

At equilibrium, the rates of the forward reaction (rate constant = [math]\displaystyle{ k_f }[/math]) and reverse reaction (rate constant = [math]\displaystyle{ k_r }[/math]) must be equivalent. Solving this equivalence yields an equilibrium dissociation constant [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math], which may be defined either as [math]\displaystyle{ k_r/k_f }[/math], or as [math]\displaystyle{ [R][L]/[C] }[/math], where brackets indicate the molar concentration of a species. Meanwhile, the fraction of receptors that are bound to ligand at equilibrium, often called y, is [math]\displaystyle{ C/R_{TOT} }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ R_{TOT} }[/math] indicates total (both bound and unbound) receptors. Note that the position of the equilibrium (i.e., y) depends on the starting concentrations of the reactants; however, [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math] is always the same value. The total number of receptors [math]\displaystyle{ R_{TOT} }[/math]= [C] (ligand-bound receptors) + [R] (unbound receptors). Thus,

[math]\displaystyle{ \qquad y = {[C] \over R_{TOT}} \qquad = \qquad {[C] \over [C] + [R]} \qquad = \qquad {[L] \over [L] + [K_D]} \qquad }[/math]

where the right-hand equation was derived by algebraic substitution. If the ligand concentration is in excess of that of the receptor, [L] may be approximated as a constant, L, for any given equilibrium. Let’s explore the implications of this result:

- What happens when L << [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]?

- →Then y ~ [math]\displaystyle{ L/K_D }[/math], and the binding fraction increases in a first-order fashion, directly proportional to L.

- What happens when L >> [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]?

- →In this case y ~1, so the binding fraction becomes approximately constant, and the receptors are saturated.

- What happens when L = [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]?

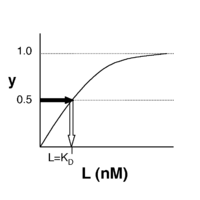

- →Then y = 0.5, and the fraction of receptors that are bound to ligand is 50%. This is why you can read [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math] directly off of the plots in Nagai’s paper (compare Figure 3 and Table 1). When y = 0.5, the concentration of free calcium (our [L]) is equal to [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]. This is a great rule of thumb to know.

The figures at right demonstrate how to read [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math] from binding curves. You will find semilog plots (bottom) particularly useful today, but the linear plot (top) can be a helpful visualization as well. Keep in mind that every L value is associated with a particular equilbrium value of y, while the curve as a whole gives information on the global equilibrium constant [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math].

Of course, inverse pericam has multiple binding sites, and thus IPC-calcium binding is actually more complicated than in the example above. The [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math] reported by Nagai is called an ‘apparent [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]’ because it reflects the overall avidity of multiple calcium binding sites, not their individual affinities for calcium. Normally, calmodulin has a low affinity (N-terminus) and a high affinity (C-terminus) pair of calcium binding sites. However, the E104Q mutant, which is the version of CaM used in inverse pericam, displays low-affinity binding at both termini. Moreover, the Hill coefficient, which quantifies cooperativity of binding in the case of multiple sites, is reported to be 1.0 for inverse pericam. This indicates that calcium binds to the multiple binding sites of calmodulin indepedently of each other (in contrast to hemoglobin, for example, whose affinity for the next oxygen increases once one oxygen is bound). Thus, IPC is well-described by a single apparent [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math].

Protocols

Plan: part 1 = simplified analysis in Excel; part 2 = putting their data in curve-fitting MATLAB routines that we provide.

Part 1: Titration curve in Excel and first estimate of KD

Today you will analyze the fluorescence data that you got last time. Begin by analyzing the wild-type protein as a check on your work (your curve should resemble Nagai's Figure 3L), then move on to your mutant samples. If you are not familiar with manipulations in Excel, use the Help menu or ask the teaching faculty for assisttance.

- Open an Excel file for your data analysis. Begin by making a column of the free calcium concentrations present in your twelve test solutions. Assuming a 1:1 dilution of protein with calcium, the concentrations are: 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 250 nM, 500 nM, 750 nM, 1 μM, 10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, 1000 μM. Be sure to convert all concentrations to the same units.

- Now open the text file containing your raw data as a tab-delimited file in Excel (you can download the file from today's "talk" page). Convert the row-wise data to column-wise data (using Paste Special → Transpose), and transfer each column to your analysis file. Add column headers to indicate which protein is which. Also include a column of your control samples that did not contain protein.

- Begin by calculating the average of your blank samples, and bold this number for easy reference. It is the background fluorescence present in the calcium solutions and should be quite low. Subtract this background value from each of your raw data values. It may help to have a 3-column series called “RAW”, and another called “SUBTRACTED.”

- To get a sense of your data, you can plot the subtracted data as is and have a quick look at it. Note the approximate inflection points of the curves: these indicate the approximate values of the apparent [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math]'s.

- If your two replicate values for a given protein are wildly different, you may want to plot each curve separately. On the other hand, if your replicates are similar (as we expect), you will want to average them prior to plotting – this will improve the signal:noise of your dataset. When you do this, be sure to add error bars to your final plot.

- To get a slightly more precise value of [math]\displaystyle{ K_D }[/math], you should normalize your data to resemble Figure 3L in the Nagai paper. The maximum and minimum fluorescence values for a given protein should be defined as 100% and 0% fluorescence, respectively, and every other fluorescence value should be expressed as a percentage in between.

- Once you have analyzed the data you obtained from the fluorescence plate reader in this way, load your old Nanodrop data for the wild-type protein, and analyze it as above. How does the benchtop, single replicate assay compare to the plate reader data? (Comment on this in your notebook.)

- In class today or on your own time, prepare representative fluorescence curves for your wild-type and mutant proteins. These will be included in the data analysis portion of your portfolio.

Part 2: Improved estimate of KD using MATLAB modeling

- Double-click on the MATLAB icon to start the program.

- The workspace will open: here is where you run programs and view outputs.

- First you will have to modify the program called "Fit_Main" to include your specific data... Read the comments...

- Now return to the workspace. Type more on to better view your results. Next type Fit_Main and hit return to run this program...

For next time

- Your entire portfolio is due next time (Thursday or Friday, depending on your lab section) by 11 am. If you have been keeping up with the homework assignments, Parts 1 and 2 should be nearly done already. Please email all three parts according to the instructions.

- Please also email your finished journal club presentation to astachow AT mit DOT edu. The order in which your presentations are received will be the order of speakers. Suitable articles for presenting are here but you should not feel restricted to this list. If you have another article in mind please email me the citation for approval. Finally, don't forget to re-read the 20.109(S08):Guidelines for oral presentations.