Harmer Lab:Research: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<h3><font style="color:#4B0082;">Background</font></h3> | <h3><font style="color:#4B0082;">Background</font></h3> | ||

As one adage has it, the only constant is change. | As one adage has it, the only constant is change. A striking example of such constant change is the regular alterations in the environment caused by the daily rotation of the earth on its axis. Along with the obvious diurnal changes in light and temperature, other important environmental variables such as humidity also change on a daily basis. This periodicity in the geophysical world is mirrored by daily periodicity in the behavior and physiology of most organisms. Examples include sleep/wake cycles in animals, developmental transitions in filamentous fungi, the incidence of heart attacks in humans, and changes in organ position in plants. Many of these daily biological rhythms are controlled by the circadian clock, an internal timer or oscillator that keeps approximately 24-hour time. Less obviously, the circadian clock is also important for processes that occur seasonally, including flowering in plants, hibernation in mammals, and long-distance migration in butterflies. In fact, circadian clocks have been found in most organisms that have been appropriately investigated, ranging from photosynthetic bacteria to trees <cite>Harmer-AnnRev-2009</cite>. | ||

Circadian rhythms have been studied for hundreds of years, with plants used as the first model system (see <cite>McClung-Rev-2006</cite> for an excellent summary of the history of clock research in plants). As rooted organisms living in a continually changing world, plants are masters at withstanding environmental variation. The circadian clock is key: it both ensures the optimal timing of daily and seasonal events to cope with predictable stresses and regulates myriad signaling pathways to optimize responses to environmental cues. Perhaps for these reasons, the transcriptional network underlying the plant circadian oscillator is uniquely complex and a higher percentage of the transcriptome is under clock control than in other eukaryotes. In addition to regulated transcription, post-transcriptional regulation is also clearly essential for proper clock function. Our lab is interested in understanding the molecular nature of the plant circadian clock and how the clock influences plant physiology | |||

[[Image:Research fig 1.png|frame|'''Figure 1'''. Model of the plant clock. Three feedback loops (loops A - C) form a transcriptional network that regulates clock function. Also essential to clock function are post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (loop D). Many additional genes implicated in clock function have been omitted for clarity. Model from <cite>Harmer-2009</cite>; see this review for further details. ]] | [[Image:Research fig 1.png|frame|'''Figure 1'''. Model of the plant clock. Three feedback loops (loops A - C) form a transcriptional network that regulates clock function. Also essential to clock function are post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (loop D). Many additional genes implicated in clock function have been omitted for clarity. Model from <cite>Harmer-2009</cite>; see this review for further details. ]] | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

<biblio> | <biblio> | ||

# | #Harmer-AnnRev-2009 pmid=19575587 | ||

#McClung-Rev-2006 pmid=16595397 | |||

# | #Rawat-PLoSGen_2011 pmid= 21483796 | ||

# | #Hsu-eLife_2013 pmid= 23638299 | ||

#Carre-Rev-2013 pmid=23597453 | |||

# | |||

# | |||

</biblio> | </biblio> | ||

Revision as of 14:31, 28 July 2014

|

Room 2123 |

BackgroundAs one adage has it, the only constant is change. A striking example of such constant change is the regular alterations in the environment caused by the daily rotation of the earth on its axis. Along with the obvious diurnal changes in light and temperature, other important environmental variables such as humidity also change on a daily basis. This periodicity in the geophysical world is mirrored by daily periodicity in the behavior and physiology of most organisms. Examples include sleep/wake cycles in animals, developmental transitions in filamentous fungi, the incidence of heart attacks in humans, and changes in organ position in plants. Many of these daily biological rhythms are controlled by the circadian clock, an internal timer or oscillator that keeps approximately 24-hour time. Less obviously, the circadian clock is also important for processes that occur seasonally, including flowering in plants, hibernation in mammals, and long-distance migration in butterflies. In fact, circadian clocks have been found in most organisms that have been appropriately investigated, ranging from photosynthetic bacteria to trees [1]. Circadian rhythms have been studied for hundreds of years, with plants used as the first model system (see [2] for an excellent summary of the history of clock research in plants). As rooted organisms living in a continually changing world, plants are masters at withstanding environmental variation. The circadian clock is key: it both ensures the optimal timing of daily and seasonal events to cope with predictable stresses and regulates myriad signaling pathways to optimize responses to environmental cues. Perhaps for these reasons, the transcriptional network underlying the plant circadian oscillator is uniquely complex and a higher percentage of the transcriptome is under clock control than in other eukaryotes. In addition to regulated transcription, post-transcriptional regulation is also clearly essential for proper clock function. Our lab is interested in understanding the molecular nature of the plant circadian clock and how the clock influences plant physiology

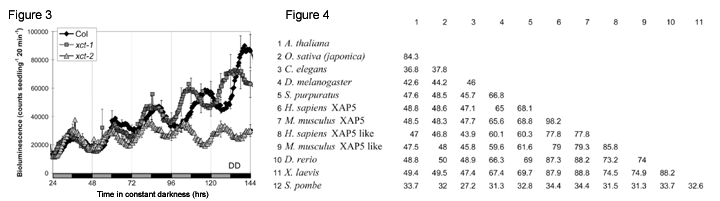

Identification of a novel clock-associated gene We use firefly luciferase driven by a clock-regulated promoter to monitor circadian rhythms in transgenic plants (Figure 2). This system has the advantage of being relatively high throughput, non-destructive, and automated. After inducing mutations in plants carrying such a luciferase reporter gene, we isolated many mutants with altered circadian rhythms [4]. One such mutant has an alteration in a gene of unknown function. When this gene, XAP5 CIRCADIAN TIMEKEEPER (XCT), is mutated, plants show altered clock function and light responses (Figure 3). Intriguingly, the C. elegans XCT homolog is essential for viability [5] and this gene is highly conserved across eukaryotes (Figure 4). Despite this high degree of conservation, the molecular function of XCT or its homologs is currently unknown. We are using genetic and biochemical approaches in Arabidopsis and S. pombe to better understand the molecular function of XCT in plant clock and light signaling pathways and its fundamental biochemical role in eukaryotes.  In addition, we have carried out an enhancer screen to identify mutations that exacerbate the short-period phenotype of gi-200 plants [4]. One such enhancer of gi (egi) mutant has been mapped to a region of the genome with no known clock genes, suggesting it represents a new locus involved in clock function. We are currently using positional cloning to molecularly identify this gene. Clock regulation of plant physiology We are interested in how the clock influences plant physiology at both the mechanistic and descriptive levels. What processes are influenced by the clock? How does the clock regulate its many outputs so that each occurs at the most appropriate time of day? We have taken a genomic approach to address both kinds of questions. Using DNA microarrays, we have found that in young seedlings grown in constant light and temperature, at least 30% of expressed genes show circadian variation in steady-state mRNA levels [7, 8]. Peak expression of these genes occurs at a wide range of times, just as clock regulated physiological pathways show peak activity at diverse times of day. We have taken advantage of the large number of gene expression profiling experiments carried out in Arabidopsis to identify pathways that might be clock regulated. We found that clock-regulated genes are over-represented among all of the classical plant hormone and multiple stress response pathways, suggesting that all of these pathways are influenced by the circadian clock [7] (Figure 5).

Bibliography

|