Molecular Recognition Laboratorium: Difference between revisions

Victor Tapia (talk | contribs) |

Victor Tapia (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 330: | Line 330: | ||

Alternatively, a divergence process of the shape of the binding region may be ‘guided’ by positive selection to avoid overlapping and, thus, promiscuitive interactions. Nevertheless, the picture of linear functional pathways is being revolutionized by a more probabilistic view of a dynamical equilibrium between multiple interactions, in which “the central organizing principle is a vast and ever-shifting web of interactions, from which output is gauged by global changes in complex binding equilibria”[Mayer 2001 Apr]. Cellular systems are explained here as transformational systems in which a redundant or degenerate input is transformed into a meaningful pattern. Irun Cohen’s ‘emergent specificity’, as postulated to synthesize the clonal selection theory and our knowledge on the promiscuity of immunoreceptors[Cohen 2001; Cohen 2001; Parnes 2004], aims at stitching this fissure with nonlinearity. Emergent properties are those behaviours manifested by a system when it operates as a whole, with no straightforward reducibility to the particulate components taking part in the process. | Alternatively, a divergence process of the shape of the binding region may be ‘guided’ by positive selection to avoid overlapping and, thus, promiscuitive interactions. Nevertheless, the picture of linear functional pathways is being revolutionized by a more probabilistic view of a dynamical equilibrium between multiple interactions, in which “the central organizing principle is a vast and ever-shifting web of interactions, from which output is gauged by global changes in complex binding equilibria”[Mayer 2001 Apr]. Cellular systems are explained here as transformational systems in which a redundant or degenerate input is transformed into a meaningful pattern. Irun Cohen’s ‘emergent specificity’, as postulated to synthesize the clonal selection theory and our knowledge on the promiscuity of immunoreceptors[Cohen 2001; Cohen 2001; Parnes 2004], aims at stitching this fissure with nonlinearity. Emergent properties are those behaviours manifested by a system when it operates as a whole, with no straightforward reducibility to the particulate components taking part in the process. | ||

<br><br><br> | <br><br><br> | ||

''' | }} | ||

'''REFERENCES''' {{hide| | |||

---- | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Sadowski, I, JC Stone & T Pawson (1986 Dec). A noncatalytic domain conserved among cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinases modifies the kinase function and transforming activity of Fujinami sarcoma virus P130gag-fps. Mol Cell Biol 6(12): 4396.<br> | Sadowski, I, JC Stone & T Pawson (1986 Dec). A noncatalytic domain conserved among cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinases modifies the kinase function and transforming activity of Fujinami sarcoma virus P130gag-fps. Mol Cell Biol 6(12): 4396.<br> | ||

Revision as of 06:59, 20 April 2010

Contact Information

Molecular Recognition Laboratorium,

Institute für medizinische Immunologie

CHARITÉ - UNIVERSITÄTSMEDIZIN BERLIN

Hessische Str. 3-4 D-10115 Berlin, Germany phone +49-30-450 524092 fax +49-30-450 524942 mail annette.hayungs@charite.de web charite.de

last change on 01.04.2010

Group Leader

Group Members

- Bernhard Aÿ, Postdoc

- Prisca Boisguérin, Postdoc

- Zerrin Fidan, Doktorandin

- Annette Hayungs - Secretary

- Marc Hovestädt - Doktorand

- Ines Kretzschmar - CTA

- Christiane Landgraf - CTA

- Carsten Mahrenholz - Doktorand

- Judith Müller - Doktorandin

- Livia Otte - Postdoc

- Rolf-Dietrich Stigler - IT- u. Sicherheitsbeauftragter

- Víctor Tapia - Doktorand

- Lars Vouillème - Doktorand

Research interest

Technological Development of the Peptide Array Technologies

by Victor Tapia

FIGURE

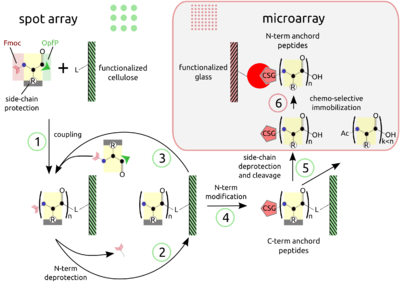

PEPTIDE ARRAYS The combination of SPOT peptide synthesis (figure A, steps 1 to 4) with

appropriate immobilization techniques on glass supports (figure A, steps

5 and 6) is wide spread. The SPOT technology provides low-scale but

high-throughput synthesis, while immobilization of pre-synthesized

peptides offers the benefit of a "chemical" purification step and

flexible array design. Additionally, the glass support is compatible

with fluorescence detection (see figure B, adapted from the web) and

offers the possibility to miniaturize binding assays. Beyond economy,

the later point is essential for quantitative measurements at the

steady-state of binding activity, as has been described [Ekins 1998] and

can be proven by the mass-action law.

The basic point of this technology is the simultaneous display of a

systematic collection of peptides on a planar support, on which numerous

bimolecular interaction assays can be carried out under homogeneous

conditions.

MORE

PEPTIDE ARRAYS IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF PEPTIDE SYNTHESIS

- The development of solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) by Bruce Merrifield [Gutte and Merrifield, 1969; Merrifield, 1965] and adaptions of this procedure [Fields and Noble, 1990] set the chemical ground for innovative technologies to follow.

- The development of the “Pin” method by H. Geysen [Geysen, et al., 1984] introduces the array format to peptide synthesis.

- Definitive establishment of peptide arrays came along with the development of the SPOT synthesis by Roland Frank [Frank, 1992; Frank, 2002] which simplified chemical synthesis of peptide arrays to the addressable deposition of reagents on a cellulose sheet.

Modern peptide synthesis approaches and

molecular biology make peptides accessible in a high degree of

structural diversity. The two greatest drawbacks of synthetic peptide

arrays are peptide length, with a quality threshold between 30 and 50

amino-acids, as well as the restriction to linear motives, since the

mimicry of nonlinear motives with linear peptide constructs is still

under development [Goede, et al., 2005].

PEPTIDE ARRAYS IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF BINDING ASSAY SYSTEMS

Since the 90s a major aspect of development to achieve the required

sensitivities to analyse biological samples has been the miniaturization

of analytical devices [Ekins, 1998]. It is important to note that

miniaturization is not only a matter of high-throughput and economy.

Miniaturization is an essential factor that should provide saturation of

binding sites under low analyte concentrations without significantly

altering its bulk (or ambient) concentration upon capturing [Ekins, et

al., 1990; Ekins, 1989; Joos, et al., 2002; Templin, et al., 2002].

- In this sense, the first application of a peptide microarray device in 1991, anticipating even the application of cDNA arrays, achieved already the impressive feature density of about 1024 peptides in 1.6 cm2 by means of in situ light-directed parallel synthesis [Fodor, et al., 1991].

Several methods available to generate peptide arrays on planar solid surfaces offer a range between...

- 16 peptides per cm2, in the case of SPOT macroarrays [Reimer, et al., 2002; Schutkowski, et al., 2004],

- to 2000-4000 peptides in 1.5 cm2, in the case of microarrays generated by digital photolithography [El Khoury, et al., 2007; Gao, et al., 2004; Pellois, et al., 2000; Pellois, et al., 2002].

SUPPORT MATERIALS

In order to

support synthesis, planar materials have to fulfil several requirements

including stability towards solvent and reagent deposition. The

functional groups on the surface must also be biochemically accessible

for chemical derivatisation. Furthermore, upon solid-phase binding

assay, generated peptides must be functionally displayed to allow

molecular recognition with a binding partner in the solution phase. In

particular non-specific interactions should be ruled out.

- Flexible porous supports such as cellulose [Eichler, et al., 1989; Frank and Döring, 1988], cotton [Eichler, et al., 1991; Schmidt and Eichler, 1993] or membranes [Daniels, et al., 1989; Wang and Laursen, 1992; Wenschuh, et al., 2000] are preferentially used for peptide array generation.

- Rigid, non-porous materials such as glass [Falsey, et al., 2001], gold films [Houseman and Mrksich, 2002; Jonsson, et al., 1991; Malmqvist, 1993], or silicon [Fodor, et al., 1991; Pellois, et al., 2002] have also been used for in situ synthesis, but are much more technically demanding.

- On the other side, rigid materials have a number of advantages over porous supports for functional display of molecules. Impermeability and smooth two-dimensionality of the material does not limit diffusion of the binding partner and leads to more accurate kinetics of recognition events.

- Finally the flatness and transparency of glass improve image acquisition and simplifies the use of fluorescence dyes for the read out process.

In some cases, assembled 3D structure on a non-porous surface could be

a fruitful approach. Several techniques for coherent surface modifications

are described over the past twenty years in the literature. For a comparative

overview on this field we refer to articles dedicated to the peptide and protein array

technologies [Angenendt and Glokler, 2004; Angenendt, et al., 2002;

Angenendt, et al., 2003; Seurynck-Servoss, et al., 2008;

Seurynck-Servoss, et al., 2007; Seurynck-Servoss, et al., 2007; Sobek,

et al., 2007; Sobek, et al., 2006; Wenschuh, et al., 2000].

REFERENCES

- Angenendt, P., and Glokler, J. (2004) Evaluation of antibodies and microarray coatings as a prerequisite for the generation of optimized antibody microarrays, Methods Mol Biol 264, 123-34.

- Angenendt, P., Glokler, J., Murphy, D., Lehrach, H., and Cahill, D. J. (2002) Toward optimized antibody microarrays: a comparison of current microarray support materials, Anal Biochem 309, 253-60.

- Angenendt, P., Glokler, J., Sobek, J., Lehrach, H., and Cahill, D. J. (2003) Next generation of protein microarray support materials: evaluation for protein and antibody microarray applications, J Chromatogr A 1009, 97-104.

- Daniels, S. B., Bernatowicz, M. S., Coull, J. M., and Köster, H. (1989) Membranes as solid supports for peptide synthesis., Tetrahedron Lett. 30.

- Eichler, J., Beyermann, M., and Bienert, M. (1989) Application of cellulose paper as support in simultaneous solid phase peptide synthesis., Colect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 54, 1746-52.

- Eichler, J., Bienert, M., Stierandova, A., and Lebl, M. (1991) Evaluation of cotton as a carrier for solid-phase peptide synthesis., Peptide Res. 4, 296-307.

- Ekins, R., Chu, F., and Biggart, E. (1990) Multispot, multianalyte, immunoassay, Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 48, 655-66.

- Ekins, R. P. (1989) Multi-analyte immunoassay, J Pharm Biomed Anal 7, 155-68.

- Ekins, R. P. (1998) Ligand assays: from electrophoresis to miniaturized microarrays, Clin Chem 44, 2015-30.

- El Khoury, G., Laurenceau, E., Dugas, V., Chevolot, Y., Merieux, Y., Duclos, M. C., Souteyrand, E., Rigal, D., Wallach, J., and Cloarec, J. P. (2007) Acid deprotection of covalently immobilized peptide probes on glass slides for peptide microarrays, Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2007, 2242-6.

- Falsey, J. R., Renil, M., Park, S., Li, S., and Lam, K. S. (2001) Peptide and small molecule microarray for high throughput cell adhesion and functional assays, Bioconjug Chem 12, 346-53.

- Fields, G. B., and Noble, R. L. (1990) Solid phase peptide synthesis utilizing 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids, Int J Pept Protein Res 35, 161-214.

- Fodor, S. P., Read, J. L., Pirrung, M. C., Stryer, L., Lu, A. T., and Solas, D. (1991) Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis, Science 251, 767-73.

- Frank, R. (1992) Spot-synthesis: an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support, Tetrahedron, 9217-32.

- Frank, R. (2002) The SPOT-synthesis technique: Synthetic peptide arrays on membrane supports--principles and applications, J. Immunol. Methods 267, 13-26.

- Frank, R., and Döring, R. (1988) Simultaneous multiple peptide synthesis under continuous flow conditions on cellulose paper disks as segmental solid supports, Tetrahedron 44, 6031-40.

- Gao, X., Pellois, J. P., Na, Y., Kim, Y., Gulari, E., and Zhou, X. (2004) High density peptide microarrays. In situ synthesis and applications, Mol Divers 8, 177-87.

- Geysen, H. M., Meloen, R. H., and Barteling, S. J. (1984) Use of peptide synthesis to probe viral antigens for epitopes to a resolution of a single amino acid, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81, 3998-4002.

- Goede, A., Jaeger, I. S., and Preissner, R. (2005) SUPERFICIAL--surface mapping of proteins via structure-based peptide library design, BMC Bioinformatics 6, 223.

- Gutte, B., and Merrifield, R. B. (1969) The total synthesis of an enzyme with ribonuclease A activity, J Am Chem Soc 91, 501-2.

- Houseman, B. T., and Mrksich, M. (2002) Towards quantitative assays with peptide chips: a surface engineering approach, Trends Biotechnol 20, 279-81.

- Jonsson, U., Fagerstam, L., Ivarsson, B., Johnsson, B., Karlsson, R., Lundh, K., Lofas, S., Persson, B., Roos, H., Ronnberg, I., and et al. (1991) Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology, Biotechniques 11, 620-7.

- Joos, T. O., Stoll, D., and Templin, M. F. (2002) Miniaturised multiplexed immunoassays, Curr Opin Chem Biol 6, 76-80.

- Malmqvist, M. (1993) Biospecific interaction analysis using biosensor technology, Nature 361, 186-7.

- Merrifield, R. B. (1965) Automated synthesis of peptides, Science 150, 178-85.

- Pellois, J. P., Wang, W., and Gao, X. (2000) Peptide synthesis based on t-Boc chemistry and solution photogenerated acids, J Comb Chem 2, 355-60.

- Pellois, J. P., Zhou, X., Srivannavit, O., Zhou, T., Gulari, E., and Gao, X. (2002) Individually addressable parallel peptide synthesis on microchips, Nat Biotechnol 20, 922-6.

- Reimer, U., Reineke, U., and Schneider-Mergener, J. (2002) Peptide arrays: from macro to micro, Curr Opin Biotechnol 13, 315-20.

- Schmidt, M., and Eichler, J. (1993) Multiple peptide synthesis using cellulose-based carriers: Synthesis of substance P - diastereoisomers and their histamine-releasing activity., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 3, 441-46.

- Schutkowski, M., Reimer, U., Panse, S., Dong, L., Lizcano, J. M., Alessi, D. R., and Schneider-Mergener, J. (2004) High-content peptide microarrays for deciphering kinase specificity and biology, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 43, 2671-4.

- Seurynck-Servoss, S. L., Baird, C. L., Miller, K. D., Pefaur, N. B., Gonzalez, R. M., Apiyo, D. O., Engelmann, H. E., Srivastava, S., Kagan, J., Rodland, K. D., and Zangar, R. C. (2008) Immobilization strategies for single-chain antibody microarrays, Proteomics 8, 2199-210.

- Seurynck-Servoss, S. L., Baird, C. L., Rodland, K. D., and Zangar, R. C. (2007) Surface chemistries for antibody microarrays, Front Biosci 12, 3956-64.

- Seurynck-Servoss, S. L., White, A. M., Baird, C. L., Rodland, K. D., and Zangar, R. C. (2007) Evaluation of surface chemistries for antibody microarrays, Anal Biochem 371, 105-15.

- Sobek, J., Aquino, C., and Schlapbach, R. (2007) Quality considerations and selection of surface chemistry for glass-based DNA, peptide, antibody, carbohydrate, and small molecule microarrays, Methods Mol Biol 382, 17-31.

- Sobek, J., Bartscherer, K., Jacob, A., Hoheisel, J. D., and Angenendt, P. (2006) Microarray technology as a universal tool for high-throughput analysis of biological systems, Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 9, 365-80.

- Templin, M. F., Stoll, D., Schrenk, M., Traub, P. C., Vohringer, C. F., and Joos, T. O. (2002) Protein microarray technology, Drug Discov Today 7, 815-22.

- Wang, Z., and Laursen, R. A. (1992) Multiple peptide synthesis on polypropylene membranes for rapid screening of bioactive peptides., Pep. Res. 5, 275-80.

- Wenschuh, H., Volkmer-Engert, R., Schmidt, M., Schulz, M., Schneider-Mergener, J., and Reineke, U. (2000) Coherent membrane supports for parallel microsynthesis and screening of bioactive peptides, Biopolymers 55, 188-206.

Structural Modularity in Protein-Protein Recognition

by Victor Tapia

FIGURE

Protein Interaction Domains

The organisation of living systems is a complex network of molecular interactions. Proteins are a central component of the network as they may bind to other proteins as well as to phospholipids, nucleic acids and small molecules to interconnect the diverse physiological functions of the cell. In the background of these observations, the existence of a molecular recognition code for cellular organisation is very suggestive.

MORE TEXT

Structural analysis of functional protein complexes suggests at least two classes of protein-protein interactions. In the first class, the so called surface/surface interactions, complementary rigid surfaces link the interacting partners. Under these circumstances, the residues involved in each interacting surface only come together upon protein folding. The second class consists on asymmetric or surface/string interactions, where a protein domain (folding module of moderate size that may resemble a pocket on the protein’s surface) docks a short lineal peptide motive (a peptide ligand) on the partner protein. While surface/surface interactions cannot be inferred because the primary structure is not linearly involved, the binding determinants of a protein interaction domain (PID) may be mapped to short peptides matching the sequence of the ligand peptide. The importance of these recognition domains in the formation of protein complexes by binding to short lineal peptides was firstly demonstrated in the late 1980s and early 1990s [Sadowski 1986 Dec; Mayer 1993; Ren 1993].

In a pioneering work on the kinase function and transforming activity of the Fujinami Sarcoma Virus, Sadowski et al.[Sadowski 1986 Dec] discovered “a unique domain… (which) is absent from kinases that span the plasma membrane” and concluded that “the presence of this noncatalytic domain in all known cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases of higher and lower eukaryotes argues for an important biological function... the noncatalytic domain may direct specific interactions of the enzymatic region with cellular components that regulate or mediate tyrosine kinase function”. These regions were called Src homology 2 (SH2) and 3 (SH3), the name SH1 being reserved to the catalytic region. Since then, the gained knowledge on SH2/3 domain function has been a paradigm in our understanding of PID biochemistry, e.g. PIDs as non-catalytic binding sites and with modular structure.

In this era of extensive genome sequencing, many PIDs have been discovered. The interaction partners — and, therefore, the functions of many proteins ― may be determined by identifying the critical binding sites for family members through evolutionary tracing [Lichtarge 1996 Mar 29] or mapping protein-protein interactions using functional protein arrays [Phizicky 2003 Mar 13]. Many of the PIDs in proteins can be grouped into families that show clear evidence of their evolution from a common ancestor, and genome sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Homo sapiens reveal large numbers of proteins that contain one or more common domain.

Modularity of WW PIDs

The WW domain is a well-characterized protein module that mediates specific protein-protein interactions with ligands that contain short proline-rich motifs [Bork 1994; Chen 1995; Sudol 2000]. The domain is composed of 38 amino acids, it has two signature tryptophan (W) residues, and it is one of the smallest among modular protein domains. The signature tryptophan positions are spaced 20–22 amino acids apart and have important structural role. The structure is a three beta-strand meander that forms a shallow binding pocket for proline-rich ligands (reviewed in[Sudol 2005]). In general, the folding of WW domains does not require cognate ligands or co-factors.

MORE TEXT

There are two aspects which allow a protein motiv to be recognized as module. Firstly, functional modularity: a domains ability to function independent of context, allowing transfer of function between diverse molecular systems. In the case of a WW domain, it functionally resembles the Src homology domain 3 in its recognition of proline-rich or proline-containing ligands. Based on this ligand predilection, two major and two minor groups are classified:

Group I core consensus PPxY Group II PPLP motif Group III poly-P motifs flanked by R or K Group IV short seq. with pS or pT followed by P

The involved affinity of interactions in terms of KD for polyproline rich ligands (Groups I to III) range between µM to nM values. For pSP- or pTP-containing ligands, binding strengths are measured in the low µM range.

Secondly, structural modularity: the ability of a protein motiv to be physically isolated from its protein context and yet fold into the characteristic conformation (structural autonomy). Although several WW domain structures are annotated in the Protein Database (PDB), some can only be shown to fold stabily upon ligand binding. It is a matter of controversy, if ligand binding induces the fold or if it selects a stable bounded conformation from many dynamically interchanging free conformations. This is analogous to the question whether ligand binding or folding firstly occurs.

From Promiscuous Recognition Events to Mutually Exclusive Cellular Responses

The elucidation of functional pathways of signal transduction, biochemical function or gene regulation, is firstly addressed in proteomics by deriving interaction networks depicting ideally all interactions in the cell. Several attempts have been done in this direction on different model organisms and with varied methods, including co-purification by affinity chromatography [Gavin 2002; Ho 2002; Bouwmeester 2004], yeast two-hybrid [Uetz 2000; Ito 2001], phage display, peptide array technologies [Landgraf 2004], etc. A comparison of datasets derived by individual methods demonstrates that different methods have different potential.

MORE TEXT

For example, affinity chromatographic approaches are biased to tight interactions such as those involving extensive complementary surfaces, while interactions in which one of the two partners contains at least one PID are more frequent in the two-hybrid database. The higher sensitivity of the so called synthetic approaches (yeast two-hybrid, phage display and peptide array technologies) make them better suited for detecting PID-mediated interactions since their peptide affinity in terms of KD falls in the 10 – 100 µM range (high Kd --> low affinity). However, this advantage is counterbalanced by a low specificity, especially of the yeast two-hybrid approach [Phizicky 2003].

In order to correct this deficiency a double check-up of the information fed into the interaction databases is recommended. This can be achieved by deriving two interaction networks through orthogonal (fundamentally different) synthetic methods and then considering only the intersection between the two datasets [Tong 2002; Castagnoli 2004; Landgraf 2004]. False positive reports are thus reduced if the causes for measurement error are different in each method.

The strength of this combined approach to deliver physiologically relevant interactions has been proven for a phage display/yeast two-hybrid intersected dataset [Tong 2002]. A notable conclusion of this approach is that the intersected dataset of proteins that are able to interact with a given PID is larger than expected when cellular events are viewed as a precise wiring of the proteins in the cell. Although a set of these biochemically potential binders may have no physiological relevance due to expression at different times or tissues, in vitro disrupted structures, etc., the paradox of promiscuous recognition and mutually exclusive responses seems to be inherent to PID mediated interactions: the work of Landgraf et al. [Landgraf 2004] supports the observation that a large fraction of natural peptides with the biochemical potential to bind to any given SH3 domain is actually used in vivo to mediate the formation of a complex.

An additional difficulty to derive functional interaction pathways is that the difference in affinity between ‘specific’ and ‘non-specific’ interactions has been shown to be less than two orders of magnitude in the case of SH2 and its peptide ligands [Songyang 2004]. Even when granted that the recognition specificity of intact proteins by SH3 domains is greater than for SH3-peptide recognition, affinity is not raised above one order of magnitude [Lee 1995 Oct 16; Arold 1998 Oct 20]. Moreover, the ability of a point-mutant Src SH2 domain to effectively substitute for the SH2 domain of the Sem-5 protein in activation of the Ras pathway in vivo emphasises that the specificity of Sh2-mediated interactions is not great [Marengere 1994]. Consider the later statements under the light of the fact that the affinity of the protein OppA for its ligands is in the range of two orders of magnitude (Oppa is involved in the mopping of peptides in the bacterial periplasm exhibiting no sequence specificity). Tu put it all into a nutshell: the described facts lead to a view of large and promiscuous SH-mediated interaction networks.

Since it is possible to generate mutant SH3 domains that have up to 40-fold higher affinity than their wild-types [Hiipakka 1999] , the potential of these domains as research tools and as source of lead compounds for pharmaceutical development can not be overseen. Furthermore, a question cannot be overheard in our minds: which is the functional advantage of maintaining relative low affinity and selectivity for PID-mediated interactions, instead of optimizing the potential affinity of PIDs? And further: how can PID-dependent interaction pathways achieve precise cellular responses?

A comfortable view is that sufficient effective selectivity can be brought by compartmentalization, additive effects of multiple separate interactions, cooperative assembly of multiprotein complexes, etc. and that these effects can sustain linear functional pathways. An interesting insight into this mater has been advanced by Zarrinpar, A. et al. In their work [Zarrinpar 2003 Dec 11] the authors find out that while metazoan SH3 domains may rescue the functionality of mutated Sho1-SH3 of the yeast, in the set of yeast-own SH3 domains this promiscuity is forbidden. They thus conclude and confirm that, on the background of diverging SH3 domains, negative selection has drifted the ligand sequences to non-overlapping areas of the particular SH3 binding regions on the sequence space.

Alternatively, a divergence process of the shape of the binding region may be ‘guided’ by positive selection to avoid overlapping and, thus, promiscuitive interactions. Nevertheless, the picture of linear functional pathways is being revolutionized by a more probabilistic view of a dynamical equilibrium between multiple interactions, in which “the central organizing principle is a vast and ever-shifting web of interactions, from which output is gauged by global changes in complex binding equilibria”[Mayer 2001 Apr]. Cellular systems are explained here as transformational systems in which a redundant or degenerate input is transformed into a meaningful pattern. Irun Cohen’s ‘emergent specificity’, as postulated to synthesize the clonal selection theory and our knowledge on the promiscuity of immunoreceptors[Cohen 2001; Cohen 2001; Parnes 2004], aims at stitching this fissure with nonlinearity. Emergent properties are those behaviours manifested by a system when it operates as a whole, with no straightforward reducibility to the particulate components taking part in the process.

REFERENCES

Sadowski, I, JC Stone & T Pawson (1986 Dec). A noncatalytic domain conserved among cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinases modifies the kinase function and transforming activity of Fujinami sarcoma virus P130gag-fps. Mol Cell Biol 6(12): 4396.

Mayer, BJ, R Ren, KL Clark & DS Baltimore (1993). A putative modular domain present in diverse signaling proteins. Cell 73(4): 629.

Ren, R, BJ Mayer, P Cicchetti & D Baltimore (1993). Identification of a ten-amino acid proline-rich SH3 binding site. Science 259(5098): 1157.

Lichtarge, O, HR Bourne & FE Cohen (1996 Mar 29). An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J Mol Biol 257(2): 342.

Phizicky, E, PIH Bastiaens, H Zhu, M Snyder & S Fields (2003 Mar 13). Protein analysis on a proteomic scale. Nature 422(6928): 208.

Bork, P & M Sudol (1994). The WW domain: a signalling site in dystrophin? Trends Biochem Sci 19(12): 531.

Chen, HI & M Sudol (1995). The WW domain of Yes-associated protein binds a proline-rich ligand that differs from the consensus established for Src homology 3-binding modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92(17): 7819.

Sudol, M & T Hunter (2000). NeW wrinkles for an old domain. Cell 103(7): 1001.

Sudol, M (2005). WW Domain. in Modular Protein Domains. G Cesareni, M Gimona, M Sudol and M Yaffe. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim: 502.

Gavin, AC, M Bosche, R Krause, P Grandi, M Marzioch, A Bauer, J Schultz, JM Rick, AM Michon, CM Cruciat, M Remor, C Hofert, M Schelder, M Brajenovic, H Ruffner, A Merino, K Klein, M Hudak, D Dickson, T Rudi, V Gnau, A Bauch, S Bastuck, B Huhse, C Leutwein, MA Heurtier, RR Copley, A Edelmann, E Querfurth, V Rybin, G Drewes, M Raida, T Bouwmeester, P Bork, B Seraphin, B Kuster, G Neubauer & G Superti-Furga (2002). Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415(6868): 141.

Ho, Y, A Gruhler, A Heilbut, GD Bader, L Moore, SL Adams, A Millar, P Taylor, K Bennett, K Boutilier, L Yang, C Wolting, I Donaldson, S Schandorff, J Shewnarane, M Vo, J Taggart, M Goudreault, B Muskat, C Alfarano, D Dewar, Z Lin, K Michalickova, AR Willems, H Sassi, PA Nielsen, KJ Rasmussen, JR Andersen, LE Johansen, LH Hansen, H Jespersen, A Podtelejnikov, E Nielsen, J Crawford, V Poulsen, BD Sorensen, J Matthiesen, RC Hendrickson, F Gleeson, T Pawson, MF Moran, D Durocher, M Mann, CW Hogue, D Figeys & M Tyers (2002). Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415(6868): 180.

Bouwmeester, T, A Bauch, H Ruffner, PO Angrand, G Bergamini, K Croughton, C Cruciat, D Eberhard, J Gagneur, S Ghidelli, C Hopf, B Huhse, R Mangano, AM Michon, M Schirle, J Schlegl, M Schwab, MA Stein, A Bauer, G Casari, G Drewes, AC Gavin, DB Jackson, G Joberty, G Neubauer, J Rick, B Kuster & G Superti-Furga (2004). A physical and functional map of the human TNF-alpha/NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway. Nat Cell Biol 6(2): 97.

Uetz, P, L Giot, G Cagney, TA Mansfield, RS Judson, JR Knight, D Lockshon, V Narayan, M Srinivasan, P Pochart, A Qureshi-Emili, Y Li, B Godwin, D Conover, T Kalbfleisch, G Vijayadamodar, M Yang, M Johnston, S Fields & JM Rothberg (2000). A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403(6770): 623.

Ito, T, T Chiba, R Ozawa, M Yoshida, M Hattori & Y Sakaki (2001). A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(8): 4569.

Landgraf, C, S Panni, L Montecchi-Palazzi, L Castagnoli, J Schneider-Mergener, R Volkmer-Engert & G Cesareni (2004). Protein interaction networks by proteome peptide scanning. PLoS Biol 2(1): E14.

Phizicky, E, PIH Bastiaens, H Zhu, M Snyder & S Fields (2003). Protein analysis on a proteomic scale. Nature 422(6928): 208.

Tong, AH, B Drees, G Nardelli, GD Bader, B Brannetti, L Castagnoli, M Evangelista, S Ferracuti, B Nelson, S Paoluzi, M Quondam, A Zucconi, CW Hogue, S Fields, C Boone & G Cesareni (2002). A combined experimental and computational strategy to define protein interaction networks for peptide recognition modules. Science 295(5553): 321.

Castagnoli, L, A Costantini, C Dall'Armi, S Gonfloni, L Montecchi-Palazzi, S Panni, S Paoluzi, E Santonico & G Cesareni (2004). Selectivity and promiscuity in the interaction network mediated by protein recognition modules. FEBS Lett 567(1): 74.

Songyang, Z & LC Cantley (2004). ZIP codes for delivering SH2 domains. Cell 116(2 Suppl): S41.

Lee, CH, B Leung, MA Lemmon, J Zheng, D Cowburn, J Kuriyan & K Saksela (1995 Oct 16). A single amino acid in the SH3 domain of Hck determines its high affinity and specificity in binding to HIV-1 Nef protein. EMBO J 14(20): 5006.

Arold, S, R O'Brien, P Franken, MP Strub, F Hoh, C Dumas & JE Ladbury (1998 Oct 20). RT loop flexibility enhances the specificity of Src family SH3 domains for HIV-1 Nef. Biochemistry 37(42): 14683.

Marengere, LE, Z Songyang, GD Gish, MD Schaller, JT Parsons, MJ Stern, LC Cantley & T Pawson (1994). SH2 domain specificity and activity modified by a single residue. Nature 369(6480): 502.

Hiipakka, M, K Poikonen & K Saksela (1999). SH3 domains with high affinity and engineered ligand specificities targeted to HIV-1 Nef. J Mol Biol 293(5): 1097.

Zarrinpar, A, S-H Park & WA Lim (2003 Dec 11). Optimization of specificity in a cellular protein interaction network by negative selection. Nature 426(6967): 676.

Mayer, BJ (2001 Apr). SH3 domains: complexity in moderation. J Cell Sci 114(Pt 7): 1253.

Cohen, IR (2001). Antigenic mimicry, clonal selection and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 16(3): 337.

Cohen, IR (2001). The creation of immune specificity. in Design Principles for Immune System & Other Autonomous Systems. LA Segel and IR Cohen. Oxford University Press, New York: 151–159.

Parnes, O (2004). From interception to incorporation: degeneracy and promiscuous recognition as precursors of a paradigm shift in immunology. Mol Immunol 40(14-15): 985.

Who's visiting

start on 18 Mar 2010

<html> <a href="http://www2.clustrmaps.com/counter/maps.php?url=http://openwetware.org/wiki/Molecular_Recognition_Laboratorium" id="clustrMapsLink"><img src="http://www2.clustrmaps.com/counter/index2.php?url=http://openwetware.org/wiki/Molecular_Recognition_Laboratorium" style="border:0px;" alt="Locations of visitors to this page" title="Locations of visitors to this page" id="clustrMapsImg" onerror="this.onerror=null; this.src='http://clustrmaps.com/images/clustrmaps-back-soon.jpg'; document.getElementById('clustrMapsLink').href='http://clustrmaps.com';" /> </a> </html>

Science in the city: A small series about the everyday life of scientists in berlin

FOLLOW ME >>>>