Physics307L:People/Muehlmeyer/Formal Final: Difference between revisions

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

By the early 19th century light had been established as a wave, much thanks due to the theortical and experimental accomplishments of Thomas Young and Augustine (Ohanian, 2001). At this time light was thought to be similar to sound in that it propagates through some medium. This hypothetical medium was called the "ether". Down the road, this ether led to theoretical inconsistencies with Galilean Relativity. This was shown in the famous 1881 Michelson-Morley experiment that disproved the existence of the ether by showing that the expected "ether wind" created by the earth propagating through the ether in fact has no effect on light beams (A.A Michelson, 1881). | |||

Michelson spent a considerable amount of time later in his career measuring the speed of light itself. He used a rotating mirror and prism some tens of miles away from the ligh source and measured the speed of light to be 299,794 ± 11 km/s. | |||

In 1905, Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity emerged out of the rubbles of the ether, giving new theoretical grounds for the measurement of the speed of light. Einsteins relativity is structured on two postulates-first that the laws of physics in one coordinate frame also hold in another coordinate frame moving with uniform velocity with repsect to it, and second that the velocity of light is independent of the velocity of the source (Hodgson, 1978). | |||

Since then the speed of light has been validated in numerous ways. One examples comes from the war era, with the advent of microwave cavities and radar. In 1935, Louis Essen and A.C. Gordon Smith used a microwave cavity and measured the speed of light to be 299,792 ± 3 km/s. This was done by establishing the frequency for a variety of modes of microwaves in a cavity, which of course according to Maxwell's Electro-Magnetic Theories travel at the speed of light. Knowledge fo the associated frequencies allowed them to approximate the speed of light (Wikipedia 2008). | |||

Other examples include the "space echo" of astronots on the moon. The delay of communication from the astronots during the 1972 Apollo 16 mission provided an approximate determination of the speed of light (). | |||

In this experiment we will use... | |||

Michelson, A. A., Pease, F. G., & Pearson, F. (1935). Measurement of the velocity of light in | |||

a partial vacuum. Astrophysical Journal, 82 . | |||

==Methods== | ==Methods== | ||

Revision as of 23:04, 12 December 2008

Approximating the Speed of Light via LED Emmission

Author: Justin Muehlmeyer

Experimentalists: Justin Muehlmeyer and Alexander Barron

University of New Mexico

Department of Physics and Astronomy Junior Lab November 2008

jmuehlme@unm.edu

Abstract

Is it possible to directly measure the speed of light over a distance of less than two meters? To approximate the speed of light we measured the "flight time" of pulses of light emitted by a light emitting diode by measuring the time difference between LED emission and PMT reception of the light signal down a tube via a time amplitude convertor (TAC). By varying the distance the light signal travels we plot distance vs. flight time and use the linear-least squares method to approximate the slope of our data, which gives us the speed of light. We found that our best approximation to the accepted value of 2.99 X 108 m/s was 2.91 ± .38 X 108 m/s, which came from large variations in distance and from using the "time walk" correction that accounts for the changing intensity of the light as the LED distance approaches the PMT.

Introduction

By the early 19th century light had been established as a wave, much thanks due to the theortical and experimental accomplishments of Thomas Young and Augustine (Ohanian, 2001). At this time light was thought to be similar to sound in that it propagates through some medium. This hypothetical medium was called the "ether". Down the road, this ether led to theoretical inconsistencies with Galilean Relativity. This was shown in the famous 1881 Michelson-Morley experiment that disproved the existence of the ether by showing that the expected "ether wind" created by the earth propagating through the ether in fact has no effect on light beams (A.A Michelson, 1881).

Michelson spent a considerable amount of time later in his career measuring the speed of light itself. He used a rotating mirror and prism some tens of miles away from the ligh source and measured the speed of light to be 299,794 ± 11 km/s.

In 1905, Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity emerged out of the rubbles of the ether, giving new theoretical grounds for the measurement of the speed of light. Einsteins relativity is structured on two postulates-first that the laws of physics in one coordinate frame also hold in another coordinate frame moving with uniform velocity with repsect to it, and second that the velocity of light is independent of the velocity of the source (Hodgson, 1978).

Since then the speed of light has been validated in numerous ways. One examples comes from the war era, with the advent of microwave cavities and radar. In 1935, Louis Essen and A.C. Gordon Smith used a microwave cavity and measured the speed of light to be 299,792 ± 3 km/s. This was done by establishing the frequency for a variety of modes of microwaves in a cavity, which of course according to Maxwell's Electro-Magnetic Theories travel at the speed of light. Knowledge fo the associated frequencies allowed them to approximate the speed of light (Wikipedia 2008).

Other examples include the "space echo" of astronots on the moon. The delay of communication from the astronots during the 1972 Apollo 16 mission provided an approximate determination of the speed of light ().

In this experiment we will use...

Michelson, A. A., Pease, F. G., & Pearson, F. (1935). Measurement of the velocity of light in

a partial vacuum. Astrophysical Journal, 82 .

Methods

Set Up

A long cardboard tube has the LED on one end pointing in at the PMT (Perfection Mica Company N-134 ) receiving its signals on the other end. The LED Cycles on and off at around 10KHz depending on the voltage applied (recommended voltage is around 200 volts DC). The PMT is powered by a high voltage power source at about 1900 Volts. The LED is strapped to 3 meter sticks binded by tape so that we can push the LED down the tube and measure the change in distance from its initial point. The tube is a cardboard tube wide enough to fit the PMT on one end and LED on the other. The PMT and LED each have a polarizer attached to their fronts, so that as we push the LED down the tube we can rotate the PMT on the other end to maintain a constant intensity (see segment on intensity and time walk below). The anode of the PMT is connected to the input on the delay module and to channel 1 of the digital oscilloscope (Tektronics TDS 1002).

The LED is connected to its power supply via a BNC cable. We have the LED power supply outputing 190 V. The PMT is connected via a BNC to its high voltage source outputing at 1900 V.

To measure the time difference between LED emission and PMT reception we have a time amplitude converter (TAC) which converts the time difference of its inputs into a voltage that is proportional to that time difference. The two BNC inputs are labeled the "start" time from LED emission, and the "stop" time from PMT reception through the delay module. The output ratio of the time difference between the two inputs is 10 V = 50 nS, which we read on the digital oscilloscope in channel 2.

Time Walk

Since our TAC triggers at a fixed voltage, its triggering time occurs later for small incoming amplitudes then larger ones. This created an issue because as we pushed the LED in closer to the PMT, the PMT signal increased in amplitude and the "time walk" problem then becomes a large source of systematic error. To avoid this issue we must maintain a constant PMT signal by using the polarizers to maintain constant intensity on the PMT.

The intensity was kept constant by rotating the PMT by slight amounts which rotated the polarizer covering its "lens". The polarizer "filters" or "cuts" the incoming light's electric field based on the angle that the polarizer film molecules are aligned. There is a point (or angle rather) when the polarizer cuts the incoming light entirely, and no voltage can be seen from he TAC at all. This means the alignment of the polarizer with the incoming electric field from the LED is perindicular. This is found to be of great importance, if we don't maintain a constant intensity for the PMT reception then our actual time difference will be skewed due to the fact that the TAC is receiving more signals from the PMT then it should.

Procedure and Data Methods

We varied the distance between the LED module and the photomultiplier tube, taking voltage measurements from the oscilloscope. Each trial was done with the following method:

Trial 1) Large and increasing individual Δx over large total Δx.

Trial 2) Small, constant individual Δx over small total Δx.

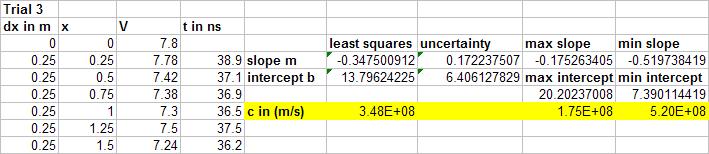

Trial 3) Large, constant individual Δx over large total Δx.

Trial 4) Medium Δx with no time walk correction.

For each Δx, we move the LED-pulse generator farther away from the PMT in specified intervals.

The raw signal from the TAC when the oscilloscope is in "sample" mode is very turbulent and quite impossible to read. The best method for data acquisition on the digital oscilloscope is using the "average" function which takes an average of the data over a set period of time. The deviation then is measured by eye, based on the fluctations of the signal from that average.

Plotting the distance vs. time and taking the slope of the line best fit line of these points via the least-squares method produced an estimate for the speed of light.

Analysis Methods

According to Taylor (see references) we determine the coefficients of a best fit linear line [math]\displaystyle{ y = A + Bx }[/math] by the relations below.

- [math]\displaystyle{ A=\frac{\sum x_i^2 \sum y_i - \sum x_i \sum x_i y_i}{\Delta_{fixed}} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{,}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \sigma_a^2 = \frac{\sigma_y^2}{\Delta_{fixed}} \sum x_i^2 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ B=\frac{N\sum x_i y_i - \sum x_i \sum y_i}{\Delta_{fixed}} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{,}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \sigma_b^2 = N \frac{\sigma_y^2}{\Delta_{fixed}} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_{fixed}=N \sum x_i^2 - \left ( \sum x_i \right )^2 }[/math]

The uncertainties in these values create an upper and lower bound for our values of the speed of light. The maximum slope is produced by adding the mean slope and the standard error of the slope. The minimum slope is the mean slope minus the standard error of the slope. The maximum and minimum y-intercepts, are the mean y-intercept plus and minus the standard error of the y-intercept, respectively.

By forcing the linear best fit line to the y-intercepts we can attain our maximum and minimum values for the speed of light when the least-squares method is implemented.

See results below.

My data analysis Excel workesheet can be accessed here:

File:Speed of Light Data Analysis Formal.xls

Tables and Results

Trial 1 Data: Distance changes increased rapidly from the initial point.

Trial 2 Data: Small changes in distance.

Trial 3 Data: Large changes in distance, but not as large as trial 1.

Trial 4 Data: was to check the importance of time walk correction. We did not use the polarizers here to correct for the changing intensity.

- All voltages were measured to have an uncertainty of ± 0.02 V due to the oscilloscope reading. This is accounted for in our data plots where on our time axis we will see error bars of ± 0.1 nS. This comes from oour TAC ratio of 10 V = 50 nS.

| Trial | Graphic Representation | Trial | Graphic Representation |

|

Trial 1: rapid and largest distance changes

Upper Error Bound:

Lower Error Bound:

|

|

Trial 2: small and constant distance changes

Upper Error Bound:

Lower Error Bound:

|

|

|

Trial 3: larger and constant distance changes

Upper Error Bound:

Lower Error Bound:

|

|

Trial 4: no time walk correction

Upper Error Bound:

Lower Error Bound:

|

|

Conclusion

The results show the importance of large changes in distance of the LED, and the necessity of the time walk correction.

Our best approximation to the true value was trial 1 with a value of [math]\displaystyle{ {c}=2.91 ± .38\cdot 10^{8}\frac{m}{s} }[/math].

This trial was characterized by changes of distance that were increasingly large, showing the importance of large changes of distance. Also of importance was the time walk correction.

Our approximation has a percent error from the actual of only 2.7 %, showing that our method was systematically accurate.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my lab partner Alexander "Der" Barron, our lab professor Dr. Steven Koch, and our lab TA, Aram Gragossian.

References

Gold, Michael. 2006. PHYSICS 307L: Junior Laboratory. The University of New Mexico, Dept. of Physics and Astronomy. [1]

Taylor, John R. 1997. An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books, 2 ed.

Wikipedia [2]

Estimating the Speed of Light from Earth-Moon Communication. David Keeports, Phys. Teach. 44, 414 (2006), DOI:10.1119/1.2353576. [3]