BIO254:Wire Together: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template:BIO254}} | {{Template:BIO254}} | ||

<div style="padding: 10px; width: 720px; border: 5px solid #B3CD4E;"> | <div style="padding: 10px; width: 720px; border: 5px solid #B3CD4E;"> | ||

==Introduction and Early History== | |||

'''Fire-Together, Wire-Together''' is a catchy phrase for a mechanism by which repeated excitation of a postsynaptic cell by a presynaptic cell causes the synapse between them to be strengthened. The story of the discovery of this mechanism begins, as most things in neuroscience do, with Santiago Ramon y Cajal. In 1894, Cajal proposed that memories could be formed by strengthening the connections between neurons to make the transmission of signal more effective. Donald Hebb elaborated on the mechanism by proposing what is now referred to as Hebb’s Rule: | |||

“Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity… tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability.… When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A's efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased” (Hebb, 1949). | “Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity… tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability.… When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A's efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased” (Hebb, 1949). | ||

This strengthening of the synaptic connection between cell A and cell B has proven to be a crucial part of neuronal wiring and plasticity. | This strengthening of the synaptic connection between cell A and cell B has proven to be a crucial part of neuronal wiring and plasticity. | ||

---- | |||

[[Image:1-F1_3.jpg]] | |||

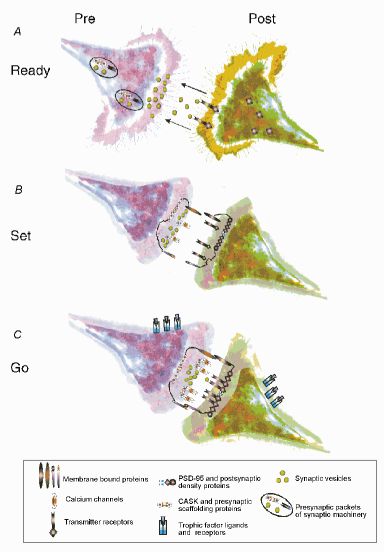

Wiring Together to Firing Together. | |||

'''A''' Binding and stimulation of postsynaptic receptors can attract appropriate target growth cones. Presynaptic packets containing synaptic machinery and channels, and postsynapatic proteins (such as PSD-95) are mobile prior to contact. | |||

'''B''' Contact between growth cones through membrane bound proteins such as neurexins/neuroligins, cadherins, and integrins, allows the stabilization of pre- and postsynaptic scaffolding proteins such as CASK and PSD-95 and mark the site for synapse formation. | |||

'''C''' Later interactions between ligands and receptors allows for maturation of the synaptic contact. This leads to clustering of calcium channels and synaptic vesicles at the presynaptic terminal, and transmitter receptors at the postsynaptic bouton. | |||

Picture Source: Munno DW and Syed NI, ''J Physiol''(2003);552:1-11 | |||

==Relevance to Neuronal Development: The Vision Pathway== | |||

A major question for developmental neuroscience is how neurons are able to specify their connections to form a network. Hebbian plasticity is one of several answers to the question, and has been studied extensively in the development of the visual pathway. Hubel and Wiesel (1979), in their landmark study of the mammalian visual system, observed that cortical areas receiving input from both eyes are segregated into alternating segments, or ocular dominance columns, that respond to inputs from only one eye. Depriving one eye of visual input during a critical period of development caused this pattern of enervation to be disrupted so that the functional eye was preferentially represented in the cortex. This suggested that an activity-dependent strengthening of synapses onto visual cortical areas is a crucial part of neuronal development in the visual system. More recent studies in the lab of Carla Shatz (Stellwagen and Shatz, 2002) have shown that this Hebbian mechanism can function much earlier in development, when spontaneous waves of activity in the retina cause strengthening of the synapses on to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus. | |||

==Relevance to Synaptic Plasticity: Learning and Memory== | |||

Fire-together, wire-together synaptic strengthening has also been essential in the study of the neuronal processes of learning and memory. Following the theories of Cajal and Hebb, Bliss and Lomo (1973) demonstrated that repeated stimulation of presynaptic cells in the perforant path of the rabbit hippocampus strengthened their connection with postsynaptic cells in the dentate gyrus. Later studies, such as those of Eric Kandel with the sea slug ''Aplysia'', correlated this form of synaptic plasticity with learning through long-term potentiation (LTP). | |||

==Current Research: Molecular Characterization== | |||

An important step in the study of neural wiring is the characterization of molecular processes that underlie Hebbian plasticity. For visual system development, one promising signaling pathway is that of the major histocompatability complex (MHC): mutations in several genes involved in the pathway disrupt the activity-dependent specification of ocular dominance columns in the LGN (Huh ''et al''., 2000). From a learning perspective, the signals that mediate the pathway from stimulation to synaptic strengthening include many cellular changes due to the influx of calcium through NMDA receptors during repeated excitation of the post-synaptic cell. Mechanisms for plasticity at the post-synaptic level include both short-term changes in the distribution of proteins at the synaptic membrane and long-term changes in protein expression, from additional receptors to structural proteins that alter synaptic structure (reviewed in Abraham and Williams, 2003). Synaptic strengthening by Hebbian mechanisms also involves pre-synaptic changes: in the hippocampus, one feature of LTP is increased vesicular release from the presynaptic terminal by a process that requires increased pre-synaptic expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Zakharenko ''et al''., 2003). These studies represent significant advances in understanding fire-together, wire-together mechanisms, but much work remains ahead to reveal the complete mechanism. | |||

==References== | |||

Abraham, W.C. and Williams, J.A. (2003) Properties and mechanisms of LTP maintenance. ''Neuroscientist'' 9, 463-474. | |||

Bliss, T.V. and Lomo, T. (1973) Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. ''Journal of Physiology'' 232, 331-356. | |||

Hebb, D.O. (1949) ''The Organization of Behavior''. Wiley, New York. | |||

Hubel, D.H. and Wiesel, T.N. (1979) Brain mechanisms of vision. ''Scientific American'' 241, 150-162. | |||

Huh, G.S., Boulanger, L.M., Du H., Riquelme, P.A., Brotz, T.M., Shatz, C.J. (2000) Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. ''Science'' 290, 2155-2159. | |||

Munno, D.W. and Syed, N.I. (2003) Synaptogenesis in the CNS: an odyssey from wiring together to firing together. ''Journal of Phisiology'' 552, 1-11 | |||

Stellwagen, D. and Shatz C.J. (2002) An instructive role for retinal waves in the development of retinogeniculate | |||

connectivity. ''Neuron'' 33, 357-367. | |||

Zakharenko, S.S., Patterson, S.L., Dragatsis, I., Zeitlin, S.O., Siegelbaum, S.A., Kandel, E.R., Morozov, A. (2003) Presynaptic BDNF required for a presynaptic but not postsynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal CA1-CA3 synapses. ''Neuron'' 39, 975-990. | |||

==<h3>Recent updates to the site:</h3>== | ==<h3>Recent updates to the site:</h3>== | ||

Latest revision as of 19:00, 6 November 2006

Introduction and Early History

Fire-Together, Wire-Together is a catchy phrase for a mechanism by which repeated excitation of a postsynaptic cell by a presynaptic cell causes the synapse between them to be strengthened. The story of the discovery of this mechanism begins, as most things in neuroscience do, with Santiago Ramon y Cajal. In 1894, Cajal proposed that memories could be formed by strengthening the connections between neurons to make the transmission of signal more effective. Donald Hebb elaborated on the mechanism by proposing what is now referred to as Hebb’s Rule: “Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity… tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability.… When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A's efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased” (Hebb, 1949). This strengthening of the synaptic connection between cell A and cell B has proven to be a crucial part of neuronal wiring and plasticity.

Wiring Together to Firing Together.

Wiring Together to Firing Together.

A Binding and stimulation of postsynaptic receptors can attract appropriate target growth cones. Presynaptic packets containing synaptic machinery and channels, and postsynapatic proteins (such as PSD-95) are mobile prior to contact.

B Contact between growth cones through membrane bound proteins such as neurexins/neuroligins, cadherins, and integrins, allows the stabilization of pre- and postsynaptic scaffolding proteins such as CASK and PSD-95 and mark the site for synapse formation.

C Later interactions between ligands and receptors allows for maturation of the synaptic contact. This leads to clustering of calcium channels and synaptic vesicles at the presynaptic terminal, and transmitter receptors at the postsynaptic bouton.

Picture Source: Munno DW and Syed NI, J Physiol(2003);552:1-11

Relevance to Neuronal Development: The Vision Pathway

A major question for developmental neuroscience is how neurons are able to specify their connections to form a network. Hebbian plasticity is one of several answers to the question, and has been studied extensively in the development of the visual pathway. Hubel and Wiesel (1979), in their landmark study of the mammalian visual system, observed that cortical areas receiving input from both eyes are segregated into alternating segments, or ocular dominance columns, that respond to inputs from only one eye. Depriving one eye of visual input during a critical period of development caused this pattern of enervation to be disrupted so that the functional eye was preferentially represented in the cortex. This suggested that an activity-dependent strengthening of synapses onto visual cortical areas is a crucial part of neuronal development in the visual system. More recent studies in the lab of Carla Shatz (Stellwagen and Shatz, 2002) have shown that this Hebbian mechanism can function much earlier in development, when spontaneous waves of activity in the retina cause strengthening of the synapses on to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus.

Relevance to Synaptic Plasticity: Learning and Memory

Fire-together, wire-together synaptic strengthening has also been essential in the study of the neuronal processes of learning and memory. Following the theories of Cajal and Hebb, Bliss and Lomo (1973) demonstrated that repeated stimulation of presynaptic cells in the perforant path of the rabbit hippocampus strengthened their connection with postsynaptic cells in the dentate gyrus. Later studies, such as those of Eric Kandel with the sea slug Aplysia, correlated this form of synaptic plasticity with learning through long-term potentiation (LTP).

Current Research: Molecular Characterization

An important step in the study of neural wiring is the characterization of molecular processes that underlie Hebbian plasticity. For visual system development, one promising signaling pathway is that of the major histocompatability complex (MHC): mutations in several genes involved in the pathway disrupt the activity-dependent specification of ocular dominance columns in the LGN (Huh et al., 2000). From a learning perspective, the signals that mediate the pathway from stimulation to synaptic strengthening include many cellular changes due to the influx of calcium through NMDA receptors during repeated excitation of the post-synaptic cell. Mechanisms for plasticity at the post-synaptic level include both short-term changes in the distribution of proteins at the synaptic membrane and long-term changes in protein expression, from additional receptors to structural proteins that alter synaptic structure (reviewed in Abraham and Williams, 2003). Synaptic strengthening by Hebbian mechanisms also involves pre-synaptic changes: in the hippocampus, one feature of LTP is increased vesicular release from the presynaptic terminal by a process that requires increased pre-synaptic expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Zakharenko et al., 2003). These studies represent significant advances in understanding fire-together, wire-together mechanisms, but much work remains ahead to reveal the complete mechanism.

References

Abraham, W.C. and Williams, J.A. (2003) Properties and mechanisms of LTP maintenance. Neuroscientist 9, 463-474.

Bliss, T.V. and Lomo, T. (1973) Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. Journal of Physiology 232, 331-356.

Hebb, D.O. (1949) The Organization of Behavior. Wiley, New York.

Hubel, D.H. and Wiesel, T.N. (1979) Brain mechanisms of vision. Scientific American 241, 150-162.

Huh, G.S., Boulanger, L.M., Du H., Riquelme, P.A., Brotz, T.M., Shatz, C.J. (2000) Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science 290, 2155-2159.

Munno, D.W. and Syed, N.I. (2003) Synaptogenesis in the CNS: an odyssey from wiring together to firing together. Journal of Phisiology 552, 1-11

Stellwagen, D. and Shatz C.J. (2002) An instructive role for retinal waves in the development of retinogeniculate connectivity. Neuron 33, 357-367.

Zakharenko, S.S., Patterson, S.L., Dragatsis, I., Zeitlin, S.O., Siegelbaum, S.A., Kandel, E.R., Morozov, A. (2003) Presynaptic BDNF required for a presynaptic but not postsynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal CA1-CA3 synapses. Neuron 39, 975-990.

Recent updates to the site:

- N

- This edit created a new page (also see list of new pages)

- m

- This is a minor edit

- b

- This edit was performed by a bot

- (±123)

- The page size changed by this number of bytes

25 April 2024

|

|

16:24 | CHEM-ENG590E:Wiki Textbook 5 changes history +75 [Courtneychau (5×)] | |||

|

|

16:24 (cur | prev) +44 Courtneychau talk contribs (→Chapter 4 - Flow Control and Mixing) | ||||

|

|

16:20 (cur | prev) +67 Courtneychau talk contribs (→Chapter 4 - Flow Control and Mixing) | ||||

|

|

16:14 (cur | prev) −36 Courtneychau talk contribs (Undo revision 1114660 by Courtneychau (talk)) Tag: Undo | ||||

|

|

16:14 (cur | prev) +27 Courtneychau talk contribs (Undo revision 1114661 by Courtneychau (talk)) Tag: Undo | ||||

|

|

16:14 (cur | prev) −27 Courtneychau talk contribs (Undo revision 1114662 by Courtneychau (talk)) Tag: Undo | ||||